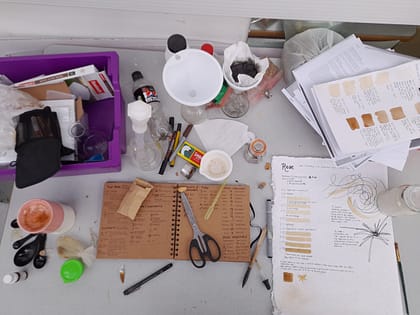

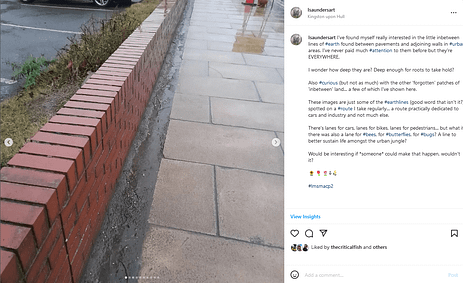

I have been posting my practical work ‘on-the-go’ on my Instagram, using the hastag #lmsmacp2 and posting the odd post or image on my online blog. However, it’s a difficult space to actually reference theory as you can’t easily provide links or cite effectively. Therefore, I’m doing a blog which highlights how the practical things I’ve been doing relate to the theory explored in my Literature Review on ‘The Geopoetics of Drawing’. I reference sections from my Literature Review in italics. The sole purpose of this post is to draw those

Although my overall conclusion was that the “Creative, scientific, material, existential, emotional and spiritual transformation – on which the survival of humanity relies – requires an integrated both/and approach to all three.”, for my Module 2 minor project I’m choosing to focus predominantly on understanding, connecting to and creatively collaborating with the non-human. In practice, this is taking many forms that touch upon a number of key themes highlighted throughout the review.

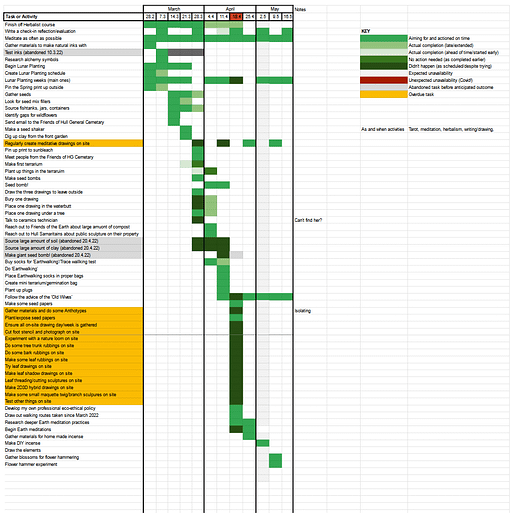

This post was originally published 8.4.2022 but I will update as I go to it to include newer explorations, up until my module hand-in date (mid-May). I have drawn attention to practical work that I feel best reflects the theme – most of this is recent, but due to the seasonality/long term nature of my practice I have also included images from last year that either illustrates ongoing practices or demonstrate how co-creations I’m starting now are ‘expected to be’ later in the year. I have also included a new coding system, which will further help connect theory to practice.

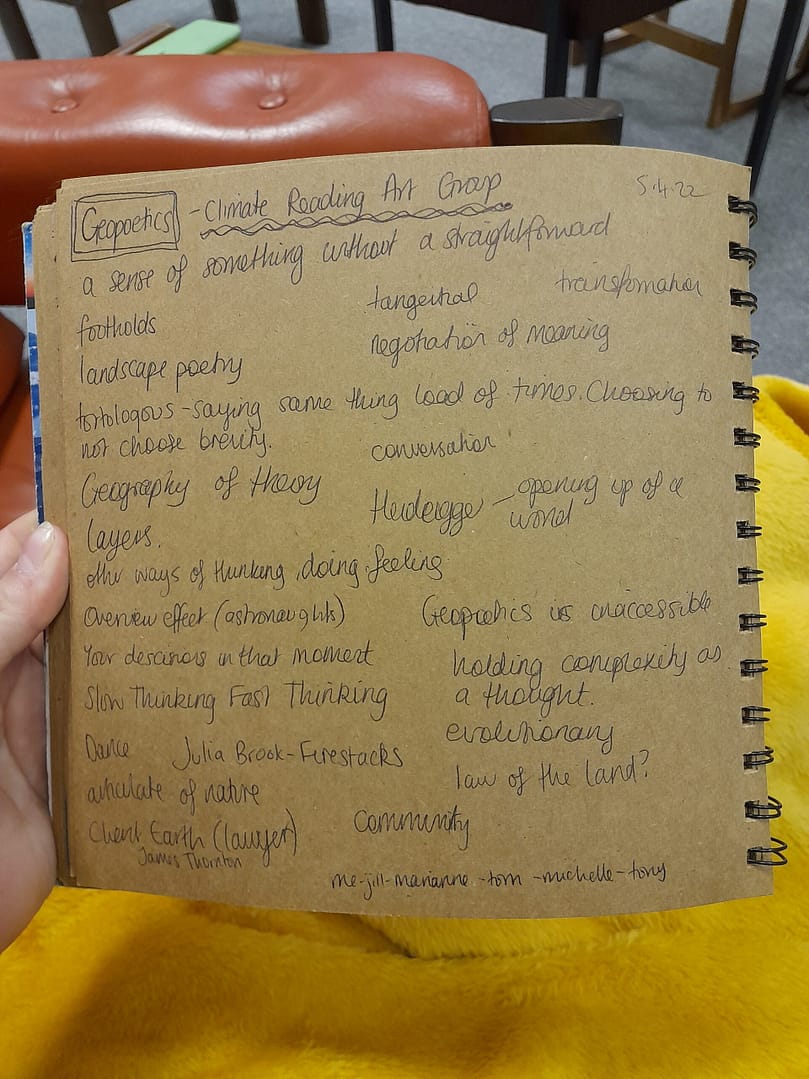

Overarching theories: Geopoetics and Dark Green Spirituality (GDGS01)

- The Scottish Centre for Geopoetics (Bell et al, 2020, p.2) offers 7 key defining elements of geopoetics: an epistemological centring of Earth; a heightened sensory and noetical awareness of Earth; an intention to overcome dualistic mind:body and human:non-human distinctions; learning from others who have sought a new approach to thinking and living; a creative, geological, geographical, philosophical, scientific or otherwise multidisciplinary expression of the Earth; multidisciplinary contributions to the wider geopoetical discourse; and, the potential for radical individual, cultural and societal renewal.

- As a multidisciplinary composite field of action, inquiry (Skinner, 2020; White, 1994b) and route-finding creative theory-practice, geopoetics encompasses multiple, holistic, creative manifestations (Magrane et al, 2020; Magrane, 2021; White, n.d.a) of: geography (Madge, 2014); space, place and landscape; language; ecological anthropospherics; Noospherics; the Anthropocene; the more/other-than-human; the human-non-human interchange and the reimagining and equitable resetting of human-nature relationships (Brownlow, 1978, cited in Ryan, 2020, p.104; Madge, 2014; Magrane et al, 2020; Magrane, 2021), any of which can be expressed creatively scientifically, existentially, emotionally and/or spiritually (Golańska and Kronenberg, 2020).

- There are three interwoven pathways to understanding the earth and kinship ethics; direct experience in Nature, the sciences and the arts (Taylor, 2021).

- Lovelock’s (1972, cited by Taylor, 2011, p.14) science-based Gaia hypothesis has been influential within “dark green” spirituality, which Taylor (2011) considers to be religion-like beliefs and practices defined by the intrinsic value of nature. Many different experiences and insights lead towards these “dark green” cosmovisions – which includes but is not limited to: cosmogony, religion, perceptions of belonging to nature, a sense of interconnected mutual dependencies, place-based human humility, environmental intrinsic valuations, kinship and loyal affection for the Earth (Taylor, 2011; 2021).

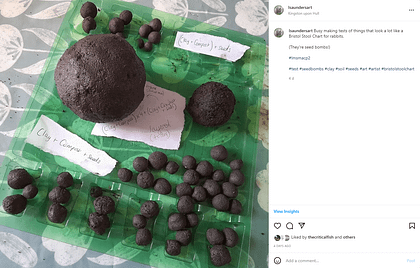

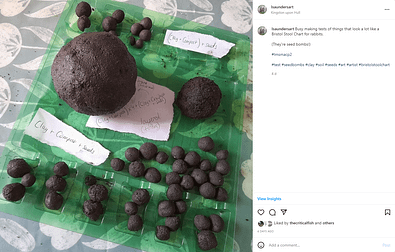

My entire practice sits within these definitions – connecting to and expressing the Earth in a multi-disciplinary way. The ethical weight I place on my practice situates it quite firmly as an expression of ‘Dark Green Spirituality’. In practice, this involves: Making:drawing, walking, gardening, direct action (e.g. seed bombing), sharing practice, meditating, free-writing:drawing, tarot, herbalism, human:non-human creative collaborations, professionally and personally connecting with related and supportive organisations (e.g. Friends of the Earth Hull, Hull General Cemetery, Scottish Centre for Geopoetics, One Hull of a Forest, Hull Trees, Hull Samaritans, The Critical Fish).

Below, I have listed key themes with a code, what other themes they relate to, images, videos and blog links that embody theory, and a table which critically links key theory:research within my Literature Review to practice-based things I’m actually doing. Underneath that, I’ve just listed some other practical things I’d like to explore at some point in future.

Direct Action (DA01)

Links to GDSG01, EE01, EPP01, HNH01, and SP01.

- Trace-walking: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/trace-walking/

- Green-guide: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/practicing-art-sustainably-and-ethically-a-green-guide/

- General blog: www.laurensaundersart.co.uk/macp2

- Instagram sharing: www.instagram.com/lsaundersart

Theory |

Practice |

| Wilson (1984, cited in Taylor, 2021, p.36) described art as a tool for discovery and artists as ‘expert observers’, both of which are able to instruct society through aesthetical ‘pleasing’. | Gardening, drawing, meditation… and sharing my practice through social media, blogging, and word of mouth.

I’m deepening my relationship with nature and showing how to positively engage with and in nature. |

| We can better discern and reply to the complex needs of the more-than-human by moving beyond mere ethical principles to embodied ethical practices (Alaimo and Hekman, 2008, cited in Coleman, 2016, p.88). | Gardening, guerilla gardening, meditating, walking, making, campaigning (Hull Friends of the Earth), making professional practice decisions.

|

| Influenced by Dewey, pedagogist Ho-Chul Lee developed a ‘living drawing’ approach to underline the relationship between aesthetic experiences and moral education. Through drawing practices, emotion, imagination and embodied reason were demonstrated to promote empathy, leading to moral reasoning and in turn moral action (Kim, 2016). | Drawing! |

In ‘Somatic Modes of Attention’, Csordas describes embodiment as ‘attending with’ or ‘to’ the body (1993, cited Hervey, 2007).

Experience and Embodiment (EE01)

Links to GDGS01, DA01, HNH01, SP01 and STEK01.

Theory |

Practice |

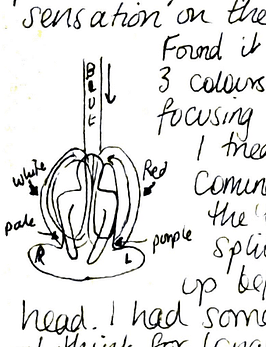

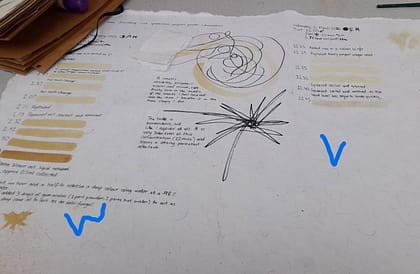

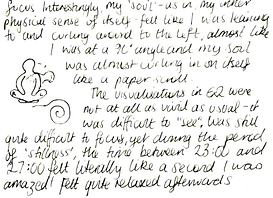

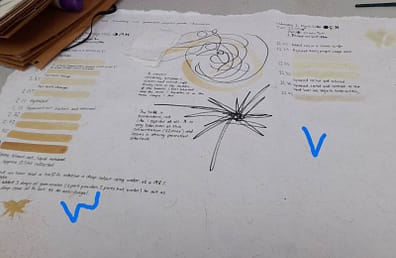

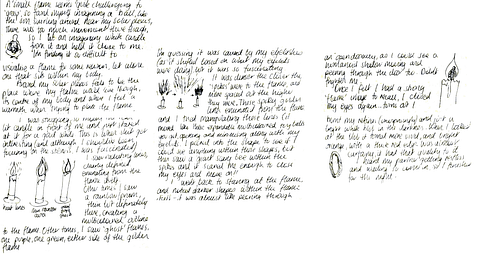

| Whitehead (1929, cited by Sjöstedt-H, 2016) suggests a panexperientialist philosophy of organism, in which perception is shared by both object and viewer in a synthetisation of mind and matter. Although Western science rejects such anthropomorphism on grounds of epistemological humility (Taylor, 2021), Caracciolo (2014, cited in Ryan, 2020, p.112) counters consciousness-attribution with consciousness-enactment, suggesting that subjects (e.g. a rock, animal, plant, landscape) can communicate in the first person by granting the reader access to its mind. Similarly, Abrams (1997) explains how the mind is understood by the Navajo people as a participatory wind as opposed to a personal possession. Therefore, all elements within an inhabited ecosystem contribute to a state of mind, which in turn, is the source of shamanistic/sorcerer gifts. | Meditation and free writing:drawing These practices encourage a shift in thinking, and spiritual:intellectual communication with the non-human. |

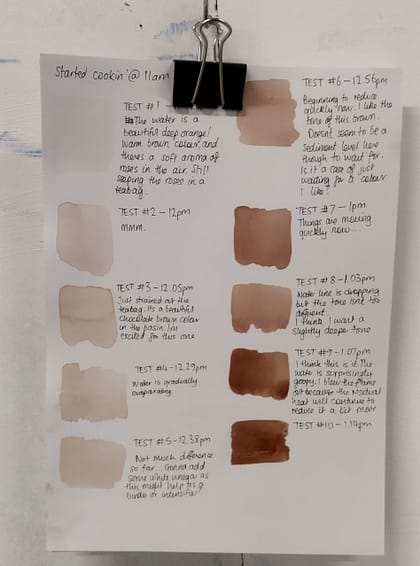

| Alaimo (2010, cited in Coleman, 2016, p.88) emphasizes the mutual entanglement of the human:non-human through literal, permeable contact zones, supporting Bachelard (1958), Lowenthal (1961, cited by Magrane, 2015, p.87-88), and White (n.d.a), who argues that it is essential for Geopoets to maintain contact between thought and feeling, idea and sensation, further underlining the importance of imagination rooted in earth-based lived experience. | Gardening, meditating in nature, handmaking natural pigment inks, making using natural materials, walking. |

| Dewey (1934, cited in McWilliam, 2008, p.32) argues that aesthetic beauty emerges from the relationship between individual and object, in what he calls ‘the experience’. The senses – of which touch is the most dominant for artists (Eames, 2008) – are the keys to experiencing the ‘landscape from within’ (Jokela, 2008). | Gardening, making using natural materials, drawing, doing. |

| Jokela (2008) reflects on the meditative, holistic and aesthetic significance of space:time interactions with nature (e.g. hunting, foraging), by examining the environment in regards to objective, emotional and textual meaning. | Gardening |

| Nature Connectedness is a field of psychological inquiry that investigates these subjective relationships with the world via contact, emotion, compassion, meaning and beauty (Lumber et al, 2017). | Gardening, meditating, making:drawing, walking. |

Other avenues to check out/develop:

- free drawing/writing exercises

Ethical Professional Practice (EPP01)

Links to GDGS01, DA01 and EE01

- Green-guide: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/practicing-art-sustainably-and-ethically-a-green-guide/

- General blog: www.laurensaundersart.co.uk/macp2

- Instagram sharing: https://www.instagram.com/lsaundersart

Theory |

Practice |

| …an intention to overcome dualistic mind:body and human:non-human distinctions; learning from others who have sought a new approach to thinking and living;multidisciplinary contributions to the wider geopoetical discourse” (Bell et all, 2020) |

Adopting more holistic approaches to practice, looking at new related artwork or reading relevant texts, sharing practice, teaching/education, engaging with residencies, engaging with other professional or community organisations, |

| We can better discern and reply to the complex needs of the more-than-human by moving beyond mere ethical principles to embodied ethical practices (Alaimo and Hekman, 2008, cited in Coleman, 2016, p.88). | Professional practice decisions, less manifestos and more manifestations in practice |

| Analogous to Nietzsche’s metaphysical concept of the artist-philosopher (White, n.d.b), artistic practice is a disruptive process of generating research that challenges dualistic approaches to knowledge that embraces new ways of thinking (Golańska and Kronenberg, 2020). | Making! Doing! Being! |

| Local identity and tradition, which are often rooted in earth-practices, are also enhanced and/or (re)constructed through the artistic embodiment of moving through nature (Jokela, 2008). | Working with local organisations or community groups, embedding heritage and local knowledge into professional work |

| However, when working within communities whom do not share one’s culture, race, language, country and/or history, it is essential to adopt a decolonised approach in order to navigate difficulties surrounding ethics, power and representation (McGiffen, 2020), as the Western approach to environmental catastrophe circles the novelty of disaster rather than acknowledge the associated historical continuity of dispossession and crisis caused by colonialism (DeLoughrey, 2019). | Accessibility, inclusion, rebalancing of power.

I can’t expect to champion voices of the Global South at this stage of my career in Hull, but I can work with marginalised or underrepresented communities within my practice. |

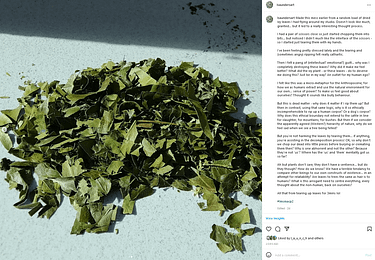

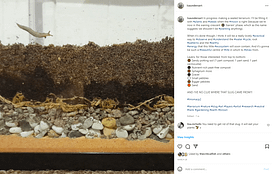

Human:non-human creative collaborations (HNH01)

Links to GDSG01, DA01, EE01, SP01 and STEK01.

Tree Drawing: https://youtube.com/shorts/6wF_QW0NaQo

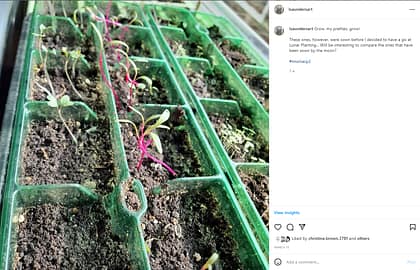

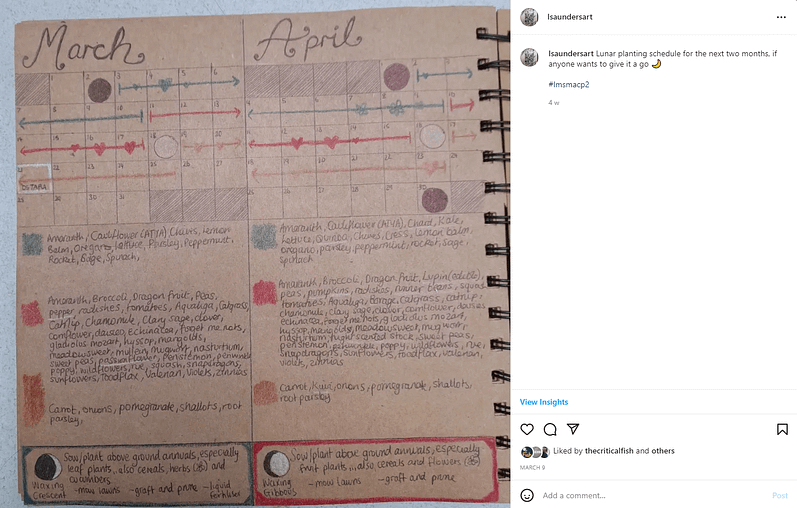

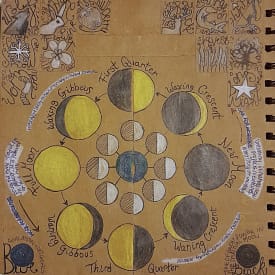

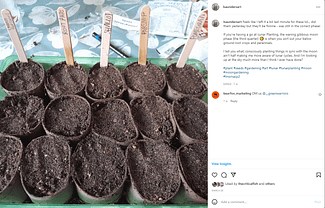

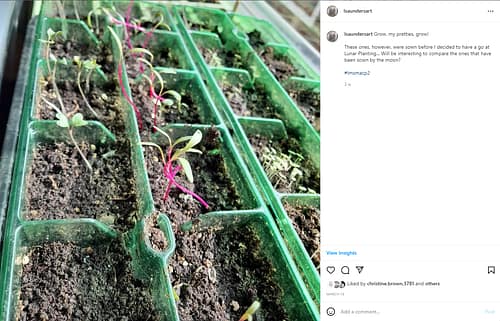

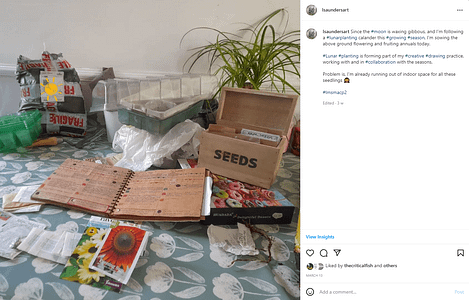

Lunar Planting: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/lunar-planting/

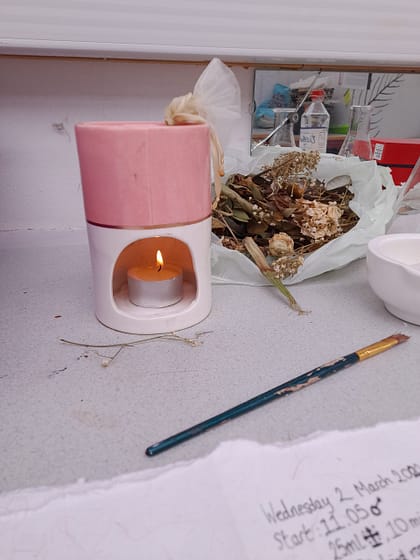

Natural Inks: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/reflective-check-in-1-inks/

Trace Walking: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/trace-walking/

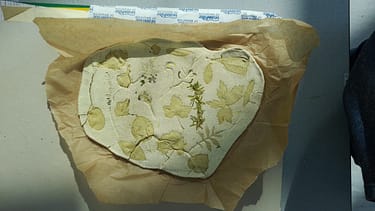

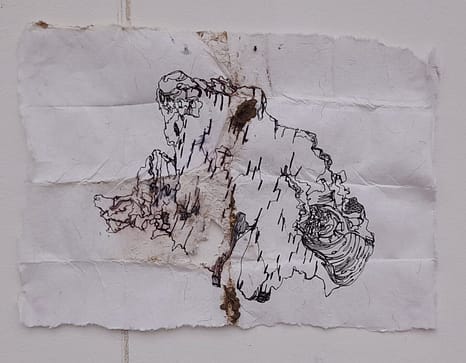

Seed Paper Making: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/seed-paper-making/

Theory |

Practice |

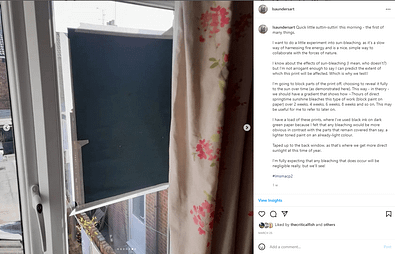

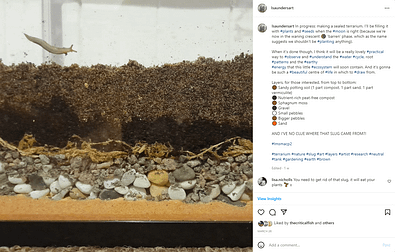

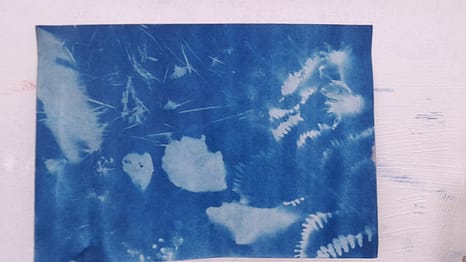

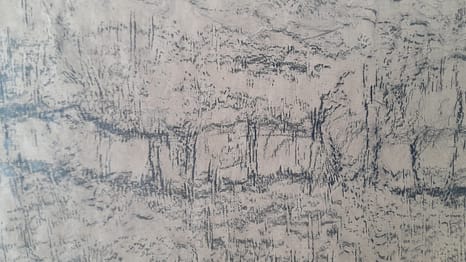

| Understanding natural phenomena as independent agencies, in which they are ‘active’ cocreators of knowledge (Barrett, 2014, cited in Golańska and Kronenberg, 2020 p.307) invites philosophical-creative potentialities between human:other-than-human artistic collaboration (Magrane, 2015), such as Louise Bourque’s burial of film (Ryan, 2020). | Sunbleaching artworks, burying artworks, leaving artworks out to the elements, domestic and guerilla gardening, wildlife photography |

| Taylor (2021) builds on the transformational potential of Leopold’s (1949, cited in ibid. p.34) Land and kinship ethics in regards to the conservation of biological diversity; creative interspecies collaboration could potentially develop revolutionary levels of appreciation towards other species (Jevbratt, 2010, cited in Ryan, 2020, p.111). | As above. |

Other avenues to check out/develop:

- Making art with the cat/dog/bird I care for

- free drawing/writing meditations

Site-specificity and Place (SP01)

Links to GDSG01, DA01, EE01, EPP01 and HNH01.

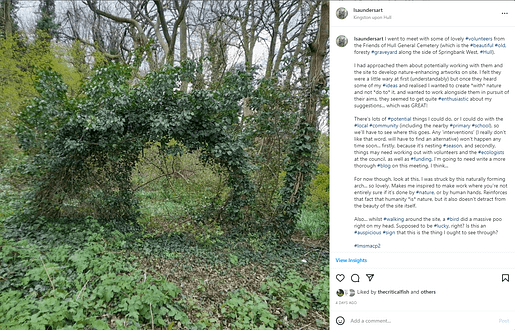

FoHGC: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/partnership-development-with-the-friends-of-hull-general-cemetery/

Trace Walking: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/trace-walking/

Theory |

Practice |

| Magrane (2015) believes that a site can be enriched and possibly recalibrated as a result of mindful immersion and subsequent geopoetic expression. | Domestic and guerilla gardening, walking, making:drawing on site, using materials found on site |

| Berman and Burnham (2016) describe how ‘Earthworks’ are eco-sensitive artificial geographic modifications in which the lands material, spatial, temporal and environmental dynamics are investigated and translated into site-specific art | Making with site-sourced materials, guerilla gardening, and site-specific sculptures in Hull General Cemetery (conversations in progress). |

| Not only does site-specific art alter how audiences perceive and engage with the space it occupies (Taïeb, 2020), but also, through interpretation, demands that the reader/viewer embody an alternative perspective (Blaeser, 2020). | As above, plus installing a living sculpture on the Hull Samaritans site (conversations in progress) |

| The coalescement of Gibson’s theory of ecological perception and Merleau-Ponty’s theory of phenomenological embodiment explains how creatively responding to a site is a form of embodiment, traces of which are left within the art (Sarkar, 2021). | As above, plus domestic gardening. |

| Poetry:Art emerges from tracking movement through space (Turnbull, 2020) through a physical:spiritual process known as ‘Transmotion’ (Vizenor, 2015, cited in Blaeser, 2020, p.39). | Working in the sites and along the routes I frequently walk. |

| The heightened awareness resulting from both observational (Ruskin, 1857, cited in Petherbridge, 2008, p.31) and site-specific drawing (Sarkar, 2021) can result in a sense of moral responsibility brought about ‘eco-literacy’ (Nelson, 2013, cited in Blaeser, 2020, p.30). | Drawing. |

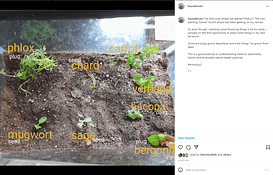

Spiritual and Traditional Ecological Knowledges (STEK01)

Links to GDSG01, DA01, EE01, and HNH01

Creative Insight (Tarot): https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/creative-insight-spread/

Lunar Planting: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/lunar-planting/

Meditations: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/meditations/

Herbalism course notes: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/herbalism-course-notes/

Theory |

Practice |

| Acknowledging that Anthropocentric critique favours Global Northern perspectives (DeLoughrey, 2019), the nature-based Reclaiming tradition of paganism criticizes and implicates the mechanistic approach of modern science with oppression, environmental destruction and colonialism. They reject the disconnection of materiality and spirit, and respond by identifying with the knowledge dismissed by religion and science (Morgain, 2013). | Lunar planting, tarot, meditation, making with natural materials whilst keeping magical associations in mind. |

| Despite Einstein expressing sorrow about the incompatibility of logical clarity and embodied truth, we need to move beyond this proliferating dualistic approach and actively pursue new visions of the future (White, 1994b). This is championed by Starhawk (1999, cited by Morgain, 2013, p.296), who encourages us to embrace contradiction with ‘both/and’ thinking as opposed to the culturally dominant ‘either/or’ mindset. | Herbalism, making practical decisions based on a balance of intuition AND reason. |

| In particular, Rawson (1969, cited in Petherbridge, 2008, p.32) defined drawing as the most ‘fundamentally spiritual’ of all creative pursuits as markmaking has a symbolic relationship with experience. | Intuitive and sensory drawing |

| Through an indigenous lens, botanist Kimmerer (2013) explores the liminal spaces between modern and traditional sciences and how human:non-human connections can cultivate more sustainable practices. | Lunar Planting, following gardening lore/TEK/old wives tales (e.g. three sisters planting) |

| The framing of the Climate Crisis has an enduring impact on how it is addressed both personally and in policy, but traditional ecological knowledge can be a useful navigational tool. Sustainability could be achieved from adopting a perspective of interdependency thus the dominant perpetuating economic-socio-political assumptions borne from the Anthropocene should be challenged (Magrane, 2018). | As above, plus adopting circular economy practices. |

Other avenues to check out/develop:

- Medieval agriculture – measuring, movement

- British TEK practices

- Ritual

References

Bell, S., Bissell, N., Kockel, U., Sutherland, C. and Watson, C. (ed.) (2020) STRAVAIG #8: Rivers and Forests (Vol. 2) [eBook] Edinburgh: The Scottish Centre for Geopoetics, p. 2. Available at: <http://www.geopoetics.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Stravaig-8-Part-2-27-May.pdf> [Accessed 1 December 2021].

Coleman, V. (2016) ‘Emergent Rhizomes: Posthumanist Environmental Ethics in the Participatory Art of Ala Plastica’, Confluencia,31(2), pp. 85 – 98

Golańska, D. and Kronenberg, A. K. (2020) ‘Creative practice for sustainability: A new materialist perspective on artivist production of eco-sensitive knowledges’, International Journal of Education through Art, 16(3), pp. 303 – 318. doi: 10.1386/eta_00035_1

Hervey, L. W (2007), ‘Embodied Ethical Descision Making’, American Journal of Dance Therapy, 29(2), pp. 93. doi: 10.1007/s10465-007-9036-5

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013) Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Madge, C. (2014) ‘On the creative (re)turn to geography: poetry, politics and passion’, Area, 46(2), pp. 178 – 185. doi: 10.1111/area.12097.

Magrane, E. (2015) ‘Situating Geopoetics’, GeoHumanities,1(1), pp. 86 – 102. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2015.1071674

Magrane, E. (2021) ‘Climate geopoetics (the earth is a composted poem)’, Dialogues in Human Geography,11(1), pp. 8 – 22. doi: 10.1177/2043820620908390.

Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (2020) ‘Geopoetics as Route Finding’. In: Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (ed.), Geopoetics in Practice,1st ed. UK, pp. 1 – 13

Ryan, J. C. (2020) ‘Seismic, or Topogorgical, Poetry’. In: Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (ed.), Geopoetics in Practice, 1st ed. UK, pp. 101-116

Saunders, L (2021) ‘The Geopoetics of Drawing’, para. 5. Available at: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/the-geopoetics-of-drawing-a-literature-review/

Skinner, J. (2020) ‘The Unbending of the Faculties; Learning from Frederick Law Olmsted’. In: Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (ed.), Geopoetics in Practice,1st ed. UK, pp. 226 – 243

White, K. (1994b) ‘Geopoetics – A Scientific Approach (Extract from Le Plateau de l’Albatros)’ [online] The International Institute of Geopoetics. Available at: https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/en/founding-texts/140-geopoetics-a-scientific-approach> [Accessed 1 December 2021].

White, K. (no date a) ‘The Great Field of Geopoetics’ [online] The International Institute of Geopoetics.Available at: <https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/en/founding-texts/133-the-great-field-of-geopoetics> [Accessed 1 December 2021].