I wrote posts back in April and November last year explaining how my practical work at the time connected to the theory I had researched within my Literature Review (The Geopoetics of Drawing’ and subsequent journal article (Ethical Art-Making – Human:Non-Human Creative Collaborations). It was very helpful to connect disperate ‘on-the-go’ posts on Instagram – where I couldn’t really reference theory/provide links easily – to other random blogs, practical work and meaningful evaluation/reflection.

Well, now I’m wrapping up my MA all this time later, everything has evolved with new experiences, new thoughts, new research, new connections and new making practices.

I reference sections from my literature review and journal article in italics, and will continue to use and include the coding system I used previously in meta-posts which will further help connect theory to practice throughout my entire MA journey (as opposed to simply between Module 4 and 5). I’ll try and not repeat myself too much, as much of what I’m doing now sits under the umbrella of Geopoetics (so it’s all still relevant), but I have directly copied and pasted all the theory parts from my previous writings for the benefit of any new readers. Module 5 has essentially been a considered expression of everything that has come before (as opposed to ‘new’ thinking and research) so admittedly a lot of the below is similar to what has been written before. Examples of work shown, however, is all new and dated from around February 2023 (when Module 5 essentially started for me).

This post should also be read in tandem with my final evaluative blog post, which offers more detail and context.

Overarching theories (Lit Review): Geopoetics and Dark Green Spirituality (GDGS01)

- The Scottish Centre for Geopoetics (Bell et al, 2020, p.2) offers 7 key defining elements of geopoetics: an epistemological centring of Earth; a heightened sensory and noetical awareness of Earth; an intention to overcome dualistic mind:body and human:non-human distinctions; learning from others who have sought a new approach to thinking and living; a creative, geological, geographical, philosophical, scientific or otherwise multidisciplinary expression of the Earth; multidisciplinary contributions to the wider geopoetical discourse; and, the potential for radical individual, cultural and societal renewal.

- As a multidisciplinary composite field of action, inquiry (Skinner, 2020; White, 1994b) and route-finding creative theory-practice, geopoetics encompasses multiple, holistic, creative manifestations (Magrane et al, 2020; Magrane, 2021; White, n.d.a) of: geography (Madge, 2014); space, place and landscape; language; ecological anthropospherics; Noospherics; the Anthropocene; the more/other-than-human; the human-non-human interchange and the reimagining and equitable resetting of human-nature relationships (Brownlow, 1978, cited in Ryan, 2020, p.104; Madge, 2014; Magrane et al, 2020; Magrane, 2021), any of which can be expressed creatively scientifically, existentially, emotionally and/or spiritually (Golańska and Kronenberg, 2020).

- There are three interwoven pathways to understanding the earth and kinship ethics; direct experience in Nature, the sciences and the arts (Taylor, 2021).

- Lovelock’s (1972, cited by Taylor, 2011, p.14) science-based Gaia hypothesis has been influential within “dark green” spirituality, which Taylor (2011) considers to be religion-like beliefs and practices defined by the intrinsic value of nature. Many different experiences and insights lead towards these “dark green” cosmovisions – which includes but is not limited to: cosmogony, religion, perceptions of belonging to nature, a sense of interconnected mutual dependencies, place-based human humility, environmental intrinsic valuations, kinship and loyal affection for the Earth (Taylor, 2011; 2021).

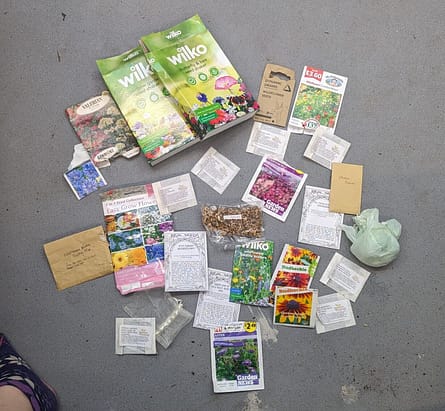

My entire practice sits within these definitions – connecting to and expressing the Earth in a multi-disciplinary way. The ethical weight I place on my practice situates it quite firmly as an expression of ‘Dark Green Spirituality’. In practice, this involves: Making:drawing, walking, gardening, direct action, sharing practice, meditating, free-writing:drawing, tarot, herbalism, human:non-human creative collaborations, professionally and personally connecting with related and supportive organisations”

Direct Action (DA01)

Links to GDSG01, EE01, EPP01, HNH01, and SP01.

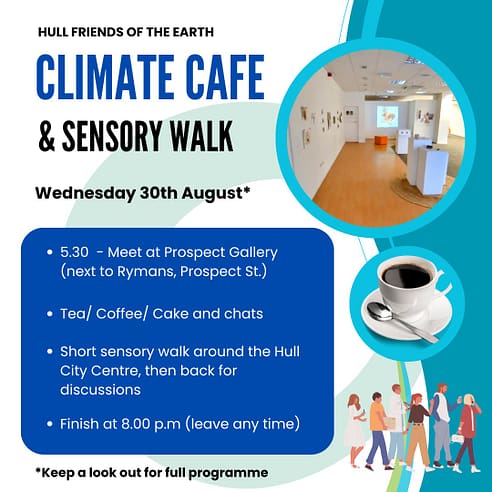

This has largely been about dissemination (e.g. workshops, blog posting), improving ecoliteracy/environmental care/nature connectedness with communities (e.g. projects, exhibition, public programme) and supporting local environmental charities. It has also been about making work which can have a positive environmental impact (i.e. the seed ball, the Where the Beings Are installation), making conscious eco-beneficial/accessible decisions in regards to my professional practice, and instigating local environmental action groups (e.g. Culture Declares Emergency Hull).

Theory (Lit Review) |

Examples in Practice |

| Wilson (1984, cited in Taylor, 2021, p.36) described art as a tool for discovery and artists as ‘expert observers’, both of which are able to instruct society through aesthetical ‘pleasing’. | The ‘seeds of change’ exhibition, the community projects, drawing, meditation… and sharing my practice through residencies, events, artist talks, instigating Culture Declares Emergency in Hull, working in schools, online social media and blogging. “I’m deepening my relationship with nature and showing how to positively engage alongside and within it.” |

| We can better discern and reply to the complex needs of the more-than-human by moving beyond mere ethical principles to embodied ethical practices (Alaimo and Hekman, 2008, cited in Coleman, 2016, p.88). | Exhibition decisions, meditating, walking, making, campaigning (Hull Friends of the Earth), instigating Culture Declares Emergency in Hull, making ethical professional practice decisions. “Working directly with nature (e.g. domestic and guerilla gardening) is a method of direct action in itself. Direct, sensual experience helps to understand the cycles, balance and needs of nature. These embodied observations shape my ethical compass (i.e. principles) and in turn, the duty I feel to take direct action and other creative moral decisions (i.e. ethical practices).” |

| Influenced by Dewey, pedagogist Ho-Chul Lee developed a ‘living drawing’ approach to underline the relationship between aesthetic experiences and moral education. Through drawing practices, emotion, imagination and embodied reason were demonstrated to promote empathy, leading to moral reasoning and in turn moral action (Kim, 2016). | Drawing!

Both with myself, and in using drawing as a vehicle in the three community projects and various community-based workshops (e.g. Explorers at 87) |

Experience and Embodiment (EE01)

Links to GDGS01, DA01, HNH01, SP01 and STEK01

Being in and with nature.

Theory (Lit Review) |

Examples in Practice |

| Whitehead (1929, cited by Sjöstedt-H, 2016) suggests a panexperientialist philosophy of organism, in which perception is shared by both object and viewer in a synthetisation of mind and matter. Although Western science rejects such anthropomorphism on grounds of epistemological humility (Taylor, 2021), Caracciolo (2014, cited in Ryan, 2020, p.112) counters consciousness-attribution with consciousness-enactment, suggesting that subjects (e.g. a rock, animal, plant, landscape) can communicate in the first person by granting the reader access to its mind. Similarly, Abrams (1997) explains how the mind is understood by the Navajo people as a participatory wind as opposed to a personal possession. Therefore, all elements within an inhabited ecosystem contribute to a state of mind, which in turn, is the source of shamanistic/sorcerer gifts. | Meditation/Listening and free writing:drawing. Engaging in telepathic and intuitive practices. Human:non-human creative collaborations. “These practices encourage a shift in thinking, and spiritual:intellectual communication with the non-human.” |

| Alaimo (2010, cited in Coleman, 2016, p.88) emphasizes the mutual entanglement of the human:non-human through literal, permeable contact zones, supporting Bachelard (1958), Lowenthal (1961, cited by Magrane, 2015, p.87-88), and White (n.d.a), who argues that it is essential for Geopoets to maintain contact between thought and feeling, idea and sensation, further underlining the importance of imagination rooted in earth-based lived experience. | Meditating in nature, using natural materials, exploring traditional ways of making (e.g. heritage and bush craft), walking, foraging, being, feeling. |

| Dewey (1934, cited in McWilliam, 2008, p.32) argues that aesthetic beauty emerges from the relationship between individual and object, in what he calls ‘the experience’. The senses – of which touch is the most dominant for artists (Eames, 2008) – are the keys to experiencing the ‘landscape from within’ (Jokela, 2008). | Making using natural materials, drawing, doing, foraging, sitting… and encouraging workshop participants to do so with me. |

| Jokela (2008) reflects on the meditative, holistic and aesthetic significance of space:time interactions with nature (e.g. hunting, foraging), by examining the environment in regards to objective, emotional and textual meaning. | #foraging265, walking, camping, sailing |

| Nature Connectedness is a field of psychological inquiry that investigates these subjective relationships with the world via contact, emotion, compassion, meaning and beauty (Lumber et al, 2017). | Meditating, making:drawing, walking, foraging, sailing, community projects |

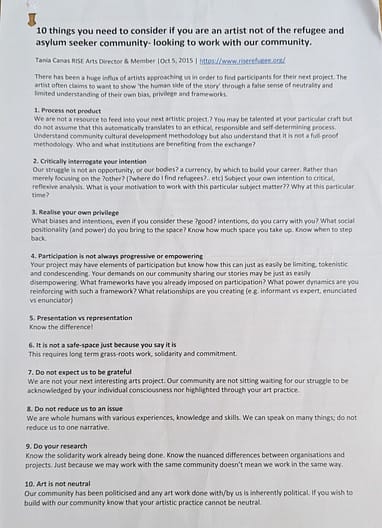

Ethical Professional Practice (EPP01)

Links to GDGS01, DA01 and EE01

Similar to DA01 in regards to dissemination, but since quitting my ‘proper job’ and being a fully fledged professional artist this has become much more about the professionalization of practice (e.g. residencies, teaching on the subject to young people, workshops, and making decisions around exhibition) and the development of paid project work (e.g. A Space to Be, Shorelines, Riverspeaking). For me, this theme has also very been about exploring the what NOT to do, what DOESN’T feel right to do as much as engaging in best practice. It’s been about how to make work in the most equitable way that I can, where ownership and credit is shared with participants (both human and non-human ones) and acting in a way that isn’t exploitative or inaccessible. For me, Ethical Professional Practice also extends to making choices which go beyond the visible practice… such as choosing to do my business banking with an ethical provider, using materials I already have or buying things second-hand, and so on. I have held myself accountable to an Environmental Policy for years, which can be read HERE.

Theory (Lit Review) |

Practice |

| …an intention to overcome dualistic mind:body and human:non-human distinctions; learning from others who have sought a new approach to thinking and living;multidisciplinary contributions to the wider geopoetical discourse” (Bell et all, 2020) |

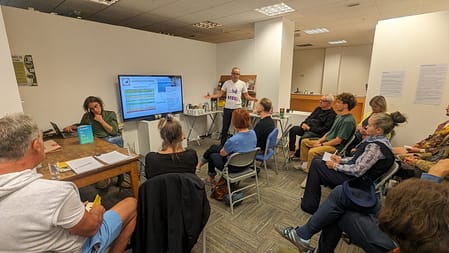

Adopting more holistic approaches to practice, looking at new related artwork, reading relevant texts, sharing practice, discussing themes (e.g. in CRAG), teaching young people, engaging with residencies, doing artist talks, learning heritage crafts from other practitioners, engaging with other professional organisations and community groups. |

| We can better discern and reply to the complex needs of the more-than-human by moving beyond mere ethical principles to embodied ethical practices (Alaimo and Hekman, 2008, cited in Coleman, 2016, p.88). | Professional practice decisions, really thinking about what materials and processes I’m using.

Identifying what creative processes ARE more environmentally ethical and which ones ARE NOT Trying to act with the least negative environmental impact way in putting on my final exhibition (e.g. borrowing, renting, minimising plastic use, sustaining life within) |

| Analogous to Nietzsche’s metaphysical concept of the artist-philosopher (White, n.d.b), artistic practice is a disruptive process of generating research that challenges dualistic approaches to knowledge that embraces new ways of thinking (Golańska and Kronenberg, 2020). | Making, doing and being. |

| Local identity and tradition, which are often rooted in earth-practices, are also enhanced and/or (re)constructed through the artistic embodiment of moving through nature (Jokela, 2008). | Embedding heritage and local knowledge into professional work by working alongside local schools, cultural and activist organisations and community groups – local identity has been key in developing community projects. Seeking to learn earth-practices native to Great Britain (i.e. heritage craft) |

| However, when working within communities whom do not share one’s culture, race, language, country and/or history, it is essential to adopt a decolonised approach in order to navigate difficulties surrounding ethics, power and representation (McGiffen, 2020), as the Western approach to environmental catastrophe circles the novelty of disaster rather than acknowledge the associated historical continuity of dispossession and crisis caused by colonialism (DeLoughrey, 2019). | Accessibility, inclusion, rebalancing of power.I’ll be working co-creatively with various under-represented groups across the environmental discourse within each of my community projects (e.g. disabled people, young people, working class, refugee and asylum seekers).

I believe in the importance of promoting those voices (in the context of climate justice) and part of the reason why I’ve involved/included others within my MA show. |

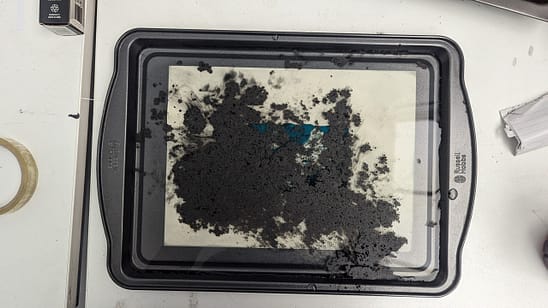

Human:non-human creative collaborations (HNH01 and HNH02)

Links to GDSG01, DA01, EE01, SP01 and STEK01.

Theory (Lit Review) |

Examples in Practice |

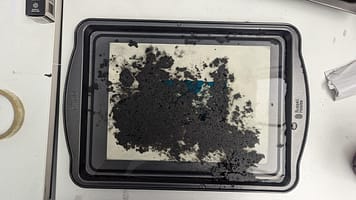

| Understanding natural phenomena as independent agencies, in which they are ‘active’ cocreators of knowledge (Barrett, 2014, cited in Golańska and Kronenberg, 2020 p.307) invites philosophical-creative potentialities between human:other-than-human artistic collaboration (Magrane, 2015), such as Louise Bourque’s burial of film (Ryan, 2020). | Making artworks using naturally occurring materials, working with natural processes, burying works, submerging works, exposing works.

Mental shift of truly acknowledging the creative agency of the non-human and embracing what that means morally and philosophically. |

| Taylor (2021) builds on the transformational potential of Leopold’s (1949, cited in ibid. p.34) Land and kinship ethics in regards to the conservation of biological diversity; creative interspecies collaboration could potentially develop revolutionary levels of appreciation towards other species (Jevbratt, 2010, cited in Ryan, 2020, p.111). | As above. And making it as clear as possible in communication with others that this is what I’m doing / hoping. |

Theory / Artist Practice (Journal)

|

Examples in Practice |

| Whilst non-human beings have been creatively acknowledged, it is typically to use them as material or symbolic interfaces to produce something reflective of the ‘artist’s intentionality, intuition and interpretation’ (Cypher, 2017). Live animals appear ‘primarily as muse, motif, material, model and medium’, ‘consumed as exhibition pieces, manipulated as objects of study or pure spectacle, rendered as material or anthromorphised’ (Ullrich, 2019). They may also experience captivity:restraint:control, use human tools when ‘working’ in human environments, or made to engage in human behaviours without understanding the human context. In this way, non-humans frequently have their creative agency dismissed, anthropocentrically patronised or manipulated by artists (Ullrich and Trump, 2022).

Examples:

|

A Lesson in what NOT to do.

Intentionality. I have intentionally made work which ISN’T manipulated, turned into spectacle, treated purely as ‘material’, or anthromorphised, nor kept collaborators captive, restrained or controlled, made to use human tools or engage in unnatural behaviours. I’ve been so careful – through intentionality – to make work which is as respectful and ethical as possible. This isn’t always possible (e.g. using cotton in my seed balls) but I do as far as I feel practically able to and within the realms of my conscience. |

| Non-human control seems to take one of three formats: a) rearranging/training/manipulating the non-human in pursuit of human-centric aesthetics… b) to aesthetically displace:isolate entities… or c) do both

Examples:

|

Another Lesson in what NOT to do.

Relinquishing control, avoiding displacement. This is very difficult to navigate as any interaction with the non-human or natural environment could be considered ‘manipulation’. I’ve narrowed manipulation down by trying to keep forms very simple/natural – such as using circle forms as opposed to complex human forms (e.g. hearts, figurative shapes) – and not trying to make things ‘just so’ or editing the documentation of interactions to suit human aesthetics. Keeping my interaction to a minimum where possible, and if I do make an interaction, to be as ‘light-footed’ as possible or do so for overall conservational benefit. |

| There are some Interspecies Artists that involve animal participation by framing natural behaviours – including sitting, staring, singing or colour-transitioning (Deleuze, 1998, cited in Ullrich and Trump, 2022) – or otherwise not demanding anything that is unnatural for the animal(s) involved (ibid.).

Examples:

|

I’ve not asked anything or anyone (my cat, dog, plants, water, seasons, sky etc) to do anything unnatural and embracing their natural behaviours as creative expression.

The only exception has been winding cotton around the seed ball for structural integrity, or using twine to help stablise the Where the Beings Are Den… yet these were the most light touch solutions possible and are only a temporary. Embracing the extent that the storm impacted my Bergonia Storm work! Again, this is another exercise in ethical intentionality BEHIND making work instead of WHAT the work is itself. |

| Other artists simply draw attention to a core quality of their non-human collaborators.The tactile, sensory phenomenological showcasing of natural ontologies.. offer an embodied opportunity to reconnect with a singular material:entity.

Examples:

|

Simplifying work as far as possible to keep the ‘voices’ of the more-than-human entities involved clear as possible.

Making work which just showcases the beauty and power of the entity. Examples: Seed ball, evaporation drawings, HNH drawings, Documenting Erin work, Creating relatively simple drawings for the non-human to impact upon. |

| Interspecies Art should be respectful, discursive, and empowering, where animals are given some agency (including to refuse), engaged with as equal artistic co-creators, whose ‘work’ is valued even though they still might inevitability serve as an anthropocentric, artist-ego-extending tool (Ullrich, 2019). | Patience.

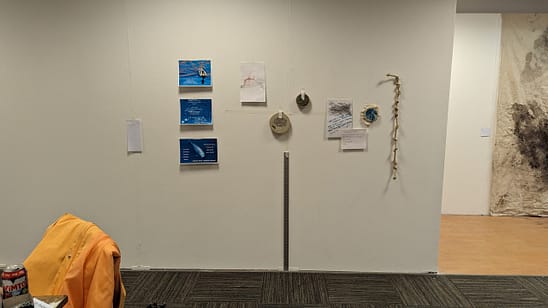

I’ve generally not tried to control outcomes in any specific way (within artistic reason), and kept that thing about ‘being given agency to refuse’ has stuck with me – if an idea doesn’t work, or doesn’t happen naturally, then it’s okay, that entity doesn’t want to work with me. Again, this practice is around intentionality and a change in perspective. I intentionally/mentally consider collaborators and equals, and as such, I’ve offered works credit as much as I can in the exhibition (e.g. titling works as ‘Collaboration with…’ and/or otherwise providing context of place, material and time) |

| Jevbratt (2009) proposes eco-sensitive collaborative methodologies, such as the use of protocols, limbic resonance, overlapping interference patterns and psychic communication (i.e. telepathy).

Examples:

|

I’ve been thinking a lot about these techniques in practice during the making of work. It’s not easy to document this in art as it’s more a cognitive shift than something that is expressed practically… but I have noticed where these processes are happening. |

| Barrett et al (2021) argues for the validity of Intuitive Interspecies Communication (IIC), a physical and psychical two-way communicative process informed by ethical protocols defined by Penelope Smith (2004, cited in ibid. p.153).

|

I’ve been exploring this process in practice, as best as possible. Not necessarily in the co-creation of work, but exploring this as a concept/practice with my cat and dog, and the plants and trees I encounter each day. |

| Actor Network Theory (ANT) (Latour, 1996;2007; Nickerson, 2022) can be used to consider how the artistic selection of materials/actors may impact knowledge production (Cypher, 2017). ANT explains that supposed human qualities – such as agency, expertise, creative intention, symbolic meaning making or social relations – are entangled with and effected by all preceding influencing non-human actors (Mark, 2017). As humans:artists:researchers, we must not place ourselves at the centre of this network, but rather consider how to best to translate our positionality, power and interconnectivity as a player therewithin (Sheehan, 2011, and May, 2022, cited in ibid. pp.122-23). | Intentionality and Awareness.

Considering what sort of voice a given entity offers within a material conversation. Shift in thinking in terms of interconnectivity My entire practice seems to be around using my positionality and power (as a human living within a human society, which I could influence to varying degrees) to translate and communicate the needs of those without a (human) voice. |

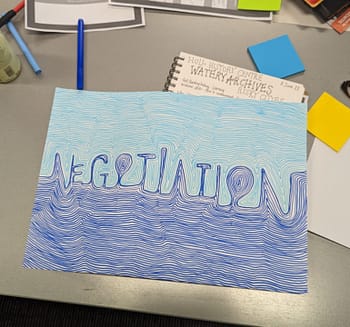

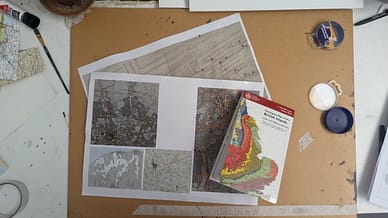

Site-specificity and Place (SP01)

Links to GDSG01, DA01, EE01, EPP01 and HNH01.

Theory |

Examples in Practice |

| Magrane (2015) believes that a site can be enriched and possibly recalibrated as a result of mindful immersion and subsequent geopoetic expression. | Walking, making:drawing on site, using materials found on site, experiencing and ‘being’ in nature, all three community projects, work made during sailing in Norfolk |

| Not only does site-specific art alter how audiences perceive and engage with the space it occupies (Taïeb, 2020), but also, through interpretation, demands that the reader/viewer embody an alternative perspective (Blaeser, 2020). | As above. The community projects, based in place, really speak to this. |

| The coalescement of Gibson’s theory of ecological perception and Merleau-Ponty’s theory of phenomenological embodiment explains how creatively responding to a site is a form of embodiment, traces of which are left within the art (Sarkar, 2021). | As above. |

| Poetry:Art emerges from tracking movement through space (Turnbull, 2020) through a physical:spiritual process known as ‘Transmotion’ (Vizenor, 2015, cited in Blaeser, 2020, p.39). | Making work in response to the sites, routes and natural materials and processes I frequently encounter. Walking, foraging365. |

| The heightened awareness resulting from both observational (Ruskin, 1857, cited in Petherbridge, 2008, p.31) and site-specific drawing (Sarkar, 2021) can result in a sense of moral responsibility brought about ‘eco-literacy’ (Nelson, 2013, cited in Blaeser, 2020, p.30). | Drawing, community projects |

Spiritual and Traditional Ecological Knowledges (STEK01 and STEK02)

Links to GDSG01, DA01, EE01, and HNH01.

This has been a focus that has been intertwined with HNH01 and HNH02. This is very much an ‘intentional’ thing (which is quite tough one to capture) alongside traditional techniques which may or may not overlap with mysticism. It’s also about the meditation and learning to listen, which again, I cannot capture on film or photo…

Theory (Lit Review, STEK01) |

Examples in Practice |

| Acknowledging that Anthropocentric critique favours Global Northern perspectives (DeLoughrey, 2019), the nature-based Reclaiming tradition of paganism criticizes and implicates the mechanistic approach of modern science with oppression, environmental destruction and colonialism. They reject the disconnection of materiality and spirit, and respond by identifying with the knowledge dismissed by religion and science (Morgain, 2013). | Tarot, meditation, making with natural materials whilst keeping magical associations in mind (e.g. ritual mat, Bergonia Storm work, choice of seeds in the seed ball), cleansing the exhibition space before each opening up, investigating ritual and magick, mentally reframing the processes of being and making with nature as ritual. |

| Despite Einstein expressing sorrow about the incompatibility of logical clarity and embodied truth, we need to move beyond this proliferating dualistic approach and actively pursue new visions of the future (White, 1994b). This is championed by Starhawk (1999, cited by Morgain, 2013, p.296), who encourages us to embrace contradiction with ‘both/and’ thinking as opposed to the culturally dominant ‘either/or’ mindset. | Making practical decisions based on a balance of intuition AND reason, science AND magick, growth AND decay. This is entwined with everything |

| In particular, Rawson (1969, cited in Petherbridge, 2008, p.32) defined drawing as the most ‘fundamentally spiritual’ of all creative pursuits as markmaking has a symbolic relationship with experience. | Intuitive and sensory drawing. I feel like everything I do is about making a mark in one way or another. |

| Through an indigenous lens, botanist Kimmerer (2013) explores the liminal spaces between modern and traditional sciences and how human:non-human connections can cultivate more sustainable practices. | As above. And practices/community work has become about ‘listening’ to learn of nature-based solutions to the climate catastrophe. |

| The framing of the Climate Crisis has an enduring impact on how it is addressed both personally and in policy, but traditional ecological knowledge can be a useful navigational tool. Sustainability could be achieved from adopting a perspective of interdependency thus the dominant perpetuating economic-socio-political assumptions borne from the Anthropocene should be challenged (Magrane, 2018). | As above, plus adopting circular practices where possible. |

Theory / Artist Practice (Journal – STEK02)

|

Examples in Practice |

| We are all indigenous to somewhere and thus carry its ancient knowledge in our cells, which we can relearn through restorative learning processes (e.g. intuitive attunement, ancient practice, stories, ritual and ceremony).

Examples:

|

Learning about ritual and engaging in different ceremonies where possible, being intentional about the symbolism or ‘magickal’ associations of non-human entities in making work.

Attempting to learn heritage craft. Learning from a local spiritual group and attending local Moots to learn more. Thinking about the ritual/ceremony present in the making of my work – in the placing of some collaborative works I’ve mentally explored ways of ‘marking’ that moment. Considering performance pieces based in ritual and ceremony – ideas around activating the Ritual Mat piece. Also ongoing tarot and meditation practice. |

References

Bell, S., Bissell, N., Kockel, U., Sutherland, C. and Watson, C. (ed.) (2020) STRAVAIG #8: Rivers and Forests (Vol. 2) [eBook] Edinburgh: The Scottish Centre for Geopoetics, p. 2. Available at: <http://www.geopoetics.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Stravaig-8-Part-2-27-May.pdf> [Accessed 1 December 2021].

Coleman, V. (2016) ‘Emergent Rhizomes: Posthumanist Environmental Ethics in the Participatory Art of Ala Plastica’, Confluencia,31(2), pp. 85 – 98

Golańska, D. and Kronenberg, A. K. (2020) ‘Creative practice for sustainability: A new materialist perspective on artivist production of eco-sensitive knowledges’, International Journal of Education through Art, 16(3), pp. 303 – 318. doi: 10.1386/eta_00035_1

Hervey, L. W (2007), ‘Embodied Ethical Descision Making’, American Journal of Dance Therapy, 29(2), pp. 93. doi: 10.1007/s10465-007-9036-5

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013) Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Madge, C. (2014) ‘On the creative (re)turn to geography: poetry, politics and passion’, Area, 46(2), pp. 178 – 185. doi: 10.1111/area.12097.

Magrane, E. (2015) ‘Situating Geopoetics’, GeoHumanities,1(1), pp. 86 – 102. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2015.1071674

Magrane, E. (2021) ‘Climate geopoetics (the earth is a composted poem)’, Dialogues in Human Geography,11(1), pp. 8 – 22. doi: 10.1177/2043820620908390.

Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (2020) ‘Geopoetics as Route Finding’. In: Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (ed.), Geopoetics in Practice,1st ed. UK, pp. 1 – 13

Ryan, J. C. (2020) ‘Seismic, or Topogorgical, Poetry’. In: Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (ed.), Geopoetics in Practice, 1st ed. UK, pp. 101-116

Saunders, L (2021) ‘The Geopoetics of Drawing’, para. 5. Available at: https://laurensaundersart.co.uk/the-geopoetics-of-drawing-a-literature-review/

Skinner, J. (2020) ‘The Unbending of the Faculties; Learning from Frederick Law Olmsted’. In: Magrane, E., Russo, L., De Leeuw, S. and Perez, C. S. (ed.), Geopoetics in Practice,1st ed. UK, pp. 226 – 243

White, K. (1994b) ‘Geopoetics – A Scientific Approach (Extract from Le Plateau de l’Albatros)’ [online] The International Institute of Geopoetics. Available at: https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/en/founding-texts/140-geopoetics-a-scientific-approach> [Accessed 1 December 2021].

White, K. (no date a) ‘The Great Field of Geopoetics’ [online] The International Institute of Geopoetics.Available at: <https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/en/founding-texts/133-the-great-field-of-geopoetics> [Accessed 1 December 2021].